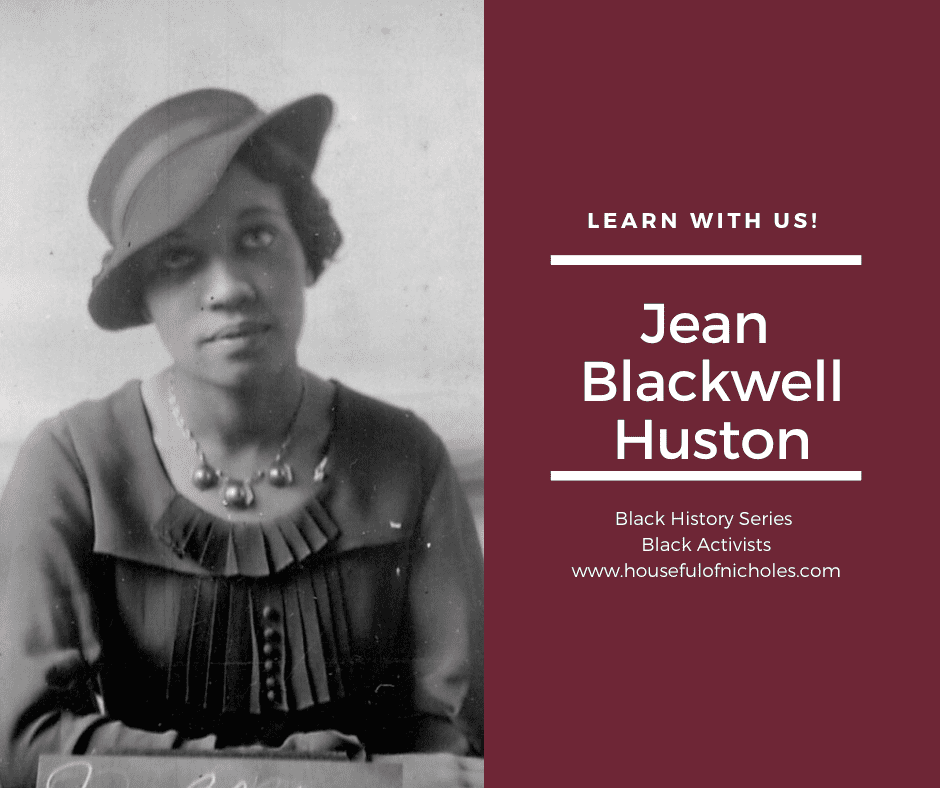

Today we introduce Jean Blackwell Hutson, an educator, archivist, and librarian whose contributions to the research and archival of African and African American artifacts were a pivotal part of our culture. She served as chief of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture from 1948-1972, bringing the standard of excellence to a level that it is STILL building upon.

We'd like to thank Regina Townsend, super librarian and owner of The Broken Brown Egg for this amazing write-up and for ALWAYS celebrating Black History no matter the month.

Jean Blackwell Huston

Jean Blackwell was born September 7, 1914 in Summerville, Florida, to Paul O. Blackwell, a farmer, and Sarah Myers Blackwell, an elementary school teacher. When she was just 4 years old, her mother Sarah moved Jean to Baltimore, Maryland, a move that would greatly impact her social trajectory. Her father Paul stayed behind in Florida to run his business, and took trips back and forth to visit his family.

While in Baltimore, Jean’s intellect and wit began to develop. In school, her ability to speed through her work caused her teachers to try and slow her down by giving her additional assignments or books to read. This only served to build a passion for reading that Jean never lost. Through her babysitter, who ran a boarding house, she was introduced to Langston Hughes, who was a college student at the time and visited Baltimore on weekends. Langston was taken with the precocious girl and began to think of and refer to her as his “little sister”.

Jean attended the all-black Frederick Douglass High School. The school sought to instill a love and importance of black history, literature, and culture into their students. To that end, some of her teachers included Yolande Du Bois (W.E.B.’s daughter), Norma Marshall (Thurgood’s mother), and acclaimed Harlem Renaissance poet and playwright May Miller. Can you IMAGINE the influence of so many influential bloodlines all connecting around this young girl’s mind?! At 15, Jean graduated valedictorian of her class, and traveled to the University of Michigan, where she planned to study psychiatry.

While at the University of Michigan, Jean was bit by the activism bug. For the past few years prior to her enrollment, a controversy regarding the school’s housing policy had been brewing. Primarily, the fact that there was NO housing provided for colored students. This unfair practice, while not uncommon, added an extreme burden to black students, who were effectively expected to not only pay their tuition, but find ways to work enough to also pay for their own room, board, and transportation to and from campus. By 1928, a local widow offered to have her boarding home inspected and approved to house colored women. It was approved and by promoting it, the school’s Dean of Women, Alice Lloyd, attempted to use this as a way to say that they had responded to the call for desegregation. By 1930, additional housing had been built, but it was still a subpar response to the outcry of black students as well as the Federated Association of Colored Women. As this fight raged, Jean was a young freshman. Later, as she recounted this time, Jean said, “I remember the bigotry of Dean Alice Lloyd. She pretended to be concerned about Negro students and wrote kind letters to parents, but she stood firm in holding the line [against integration of the dorms].

Concerned about her daughter’s sudden interest in campus politics, Jean’s mother Sarah encouraged her to leave the University of Michigan and transfer to Barnard. Once again, Sarah’s moves proved to be beneficial. Jean enjoyed her time at Barnard, becoming a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Incorporated, and graduated with her Bachelor of Arts in 1935, becoming the second black woman to do so. (My Soror Zora Neale Hurston was the first *wink*).

While Jean still wanted to pursue psychiatry, she thought a good way to help pay for medical school would be to pursue library science. She applied to the Enoch Pratt Library Training School, but was denied entrance. Knowing her skills and smarts, Jean decided that the school had not admitted her solely on the basis of her race, and decided to SUE THEM. A lawsuit that she eventually WON. But one monkey doesn’t stop a show, so in the midst of this, Jean applied and was admitted to Columbia University’s library science program. She received her Master’s in Library Science in 1936 and an additional teaching certificate from Columbia in 1941. She never left the field. So long, psychiatry.

Her first official library job was in the New York Public Library - Bronx branch. While there, one of the first things she noticed was that while much of the community’s population was Spanish-speaking, none of the books were translated. She immediately expanded the collection to include books written in Spanish, brining in a slew of Spanish-speaking residents who formerly wouldn’t use the library. In addition, she looked for other ways to both fill her time and serve the library, and began writing magazine articles to market the library’s services to the public. This was highly important, because as it is today, most library users don’t actually know how the library works, but are also extremely hesitant to ask for help. These articles made the library welcoming and personable to the community it served, and the staff approachable.

Still a friend to his “little sister”, Langston Hughs made sure to not only welcome Jean to New York, but to also introduce her to many other influential and active residents. In 1939, Jean married Andy Razaf, lyricist for Fats Waller, and she took time from the public library to utilize her teaching certificate. She served as both librarian and teacher at the Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School in her hometown of Baltimore.

Eight years later, her marriage to Andy ended in divorce, and her relationship with the New York Public Library rekindled. Back to her great ability of building on the collection and community she served, Jean was soon named the head of the Woodstock branch and part of the Division of Negro Literature. But when you’re great, opportunities keep coming, and she was soon reassigned and tasked with taking over the Schomburg collection, a special collection that had been named for Arthur Schomburg. In 1950, she married fellow librarian John Hutson, and they had a daughter, Jean Frances. Sadly, John would pass away in 1957.

Jean’s work with the Schomburg collection became the pivotal part of her career. Through her connections with her big brother Langston, Jean was able to secure both his and Richard Wright’s personal papers as part of the collection. She said that she was COMMITTED to “filing the gaps of omissions that have occurred” in the curation and telling of black history. The growth of the collection was attributed to her dedication, including spending her own money and time on additional training and research on African artifacts and history.

In 1962, she helped to develop and publish the Dictionary Catalogue of the Schomburg collection, which allowed libraries around the world to see the contents of the collection via microfilm. In 1964 her work reached international acclaim and she was invited by President of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah to the University of Ghana to curate and help to assemble their Africana Collection. She stayed in the country for a year, serving as a librarian in the University's Balme Library. She remarked to some that it was a refreshing and joyous time to be in a country where her race was cause for connection and celebration, rather than discrimination.

On her return to the US, Jean worked as an adjunct professor at the City College of New York, teaching Black studies. She also worked to help organize the Schomburg Corporation, a non-profit arm that would serve as a way to raise funding for the curation and preservation of collection and to help build a new space. As the Civil Rights movement gained speed, many would refer activists and scholars to the Schomburg because of the expanse of knowledge Jean had helped to build there.

Today, the Schomburg Collection holds 150,000 volumes, 3.5 million manuscripts, and the largest collection of photographs documenting black life IN THE WORLD, and a 16th century manuscript titled “Ad Catholicum”, written by Juan Latino and believed to be the first book written by a black man. The collection is housed in a 3.7 million dollar facility, built with the funds raised through Hutson’s Schomburg Corporation, which features five stories of red brick and glass, and an art gallery.

Aside from her work as curator of the Schomburg, Jean Hutson served as a member of the NAACP, Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., the African Studies Association, the Urban League, and the American Library Association. She held an honorary doctorate from King Memorial College, a Professional Service Award from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, and many more.

She died in Harlem at the age of 83 on February 4, 1998.